I have been trying to make sense of what is going on around the world over the last couple of weeks. George Floyd should not have died. He died because he was black. George Floyd is the tip of the iceberg. Before him there were many, many more: Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Tamir Rice, Michael Brown, Eric Garner – many of whom have not got justice despite it being years since their death.

The lives of black people have been taken so heartlessly not only by people in the US. The UK has a lot to be responsible for, apart from its own share of deaths of Black people. As Afua Hirsch said in her Guardian article last week:

The British government could have had the humility to use this moment to acknowledge Britain’s experiences. It could have discussed how Britain helped invent anti-black racism, how today’s US traces its racist heritage to British colonies in America, and how it was Britain that industrialised black enslavement in the Caribbean, initiated systems of apartheid all over the African continent, using the appropriation of black land, resources and labour to fight both world wars and using it again to reconstruct the peace.

The structural racism that causes Black people to die again and again is not what non-Black people want to discuss unless they are forced to. It is a system that has been built over years, decades, centuries, and it will take time to dismantle, if we are lucky enough to even get there. There are a bulk of resources to read on this issue – here are ways you can learn in the month of June alone, so I won’t list them all here. If you are not black and want to understand why Black Lives Matter has taken on so much urgency, please give some of them a read, watch or listen.

These discussions are hard, but they need to happen. I am far from educated enough on the subject of racism, anti-racism, structural racism, or anti-fragility – I’m still trying. Here, I want to lay out some of my thoughts on this issue, but also try and articulate something else that has been bothering me, as someone with Indian heritage.

Even as many in India raise their voices in support of Black Lives Matter, there is warranted criticism for not supporting the causes that need a lot more attention in their own backyard. (With regard to the kind of discrimination that Black people see in America, I’m talking specifically about caste discrimination – of Dalits particularly, and religious discrimination – particularly of Muslims).

There are two components to this: one, a large number of people who are getting the media attention for speaking up about Black Lives Matter in India at the moment are film celebrities, some of whom are very simply out of touch with reality (all the usual tone-deaf language about how ‘All Lives Matter’). These celebrities argue against racism in America, while endorsing fairness creams in India, and belonging to an industry which engages in ‘brownface’. You see the problem.

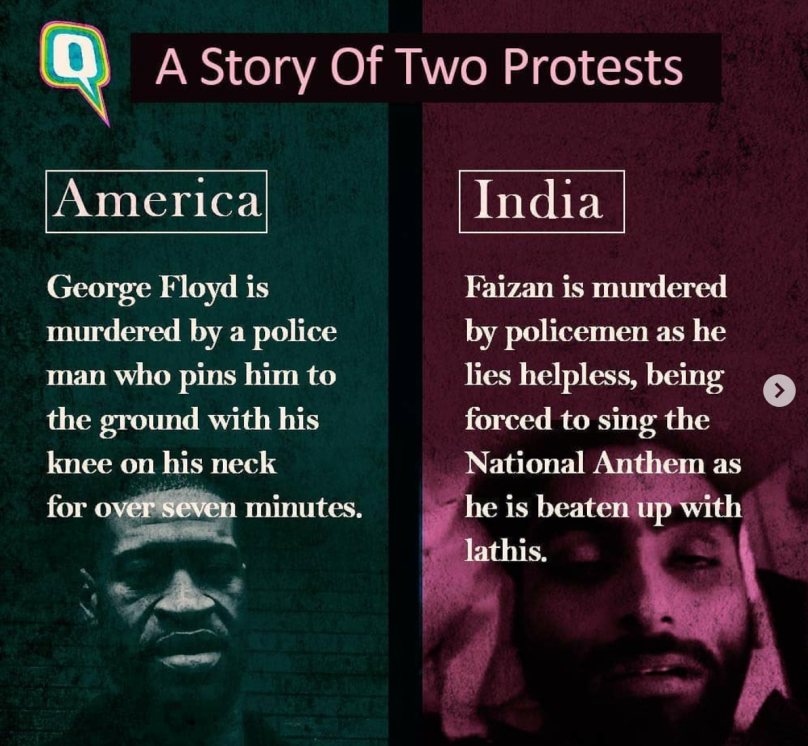

The second is the legitimacy of talking about issues in other parts of the world when there are issues to tackle at home: from a long hard look at the casteism that contributed to Dalit student Rohith Vemula’s death in 2016 to more recent instances of police overreach similar to that being witnessed in the US at the moment. As an illustration, here’s one Instagram image I’ve seen shared a lot recently:

My niece Ragini Menon recently wrote a piece worth reading, about the pathetic record Indians have with regard to the treatment of Black people, and how South Asian Americans particularly owe a lot to the work of Black communities in the US (for more on the latter, follow SouthAsians4BlackLives on Instagram). Acknowledging that many of us stand on the shoulders of Black communities is important, as is the importance of dispelling the myth of Asian-Americans as the ‘model minority’. As this NPR piece notes:

Asians have been barred from entering the U.S. and gaining citizenship and have been sent to incarceration camps, Kim pointed out, but all that is different than the segregation, police brutality and discrimination that African-Americans have endured.

Which brings me back to what made me want to explore all these things I’ve been reading, listening to and watching over the last few weeks: examining the ‘legitimacy’ of speaking up about one atrocity when there are others to acknowledge. The truth is there is no ‘convenient’ time to speak up. This is an ongoing battle; racism has been endemic for centuries. In countries like the US and UK, Black people have been facing hardships and violence for so long that many have unfortunately come to accept it as a way of life (yes, it saddens me to write that). It’s a mother’s fear of watching her son leave the house and not knowing if he’ll come back alive. It’s the fear experienced by a grown, educated Professor reduced to a shadow of his former self by the police, who stopped him in the road because of his colour. In India, Dalits and Muslims have faced this bias as well, for equally as long (a housekeeping note to anyone who wants to bring up white people or upper-caste Hindus – this is not the time or place. Please go somewhere else.)

I want to end by pointing to something that has helped me get some resolution to all these turbulent thoughts: this piece by Tamara Cofman Wittes, a Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution, who examines this alleged hypocrisy, of ‘promoting human rights when they are being trampled at home’, with reference to the US criticizing human rights abuses around the world when they are also not dealing with systemic racism at home. She concludes – and this has given me some succour – that the two aren’t mutually exclusive. You can fight for one and the other at the same time. In fact, we must. As she says:

By contrast, to insist that we must first “get our house in order” before speaking to others’ oppression, to be so ashamed by our own shortcomings that we refrain from calling out abuses abroad, and thus to withhold our solidarity from the abused, would itself be an act of moral abdication. As my friend Adham Sahloul wrote this weekend: “The people in the Hong Kong’s and Idlib’s of the world don’t have time for our spiritual reclamation sessions.” Sahloul calls for a “Yes, and” approach to American rights advocacy abroad, something that American diplomats of color, like Ambassador Nichols in Harare, already practice. Yes, we have important work to do at home. So do we all. Let’s continue reaching our hands across our borders in solidarity, and get to work.

Amen.

—

As part of my research writing this piece, I learnt of many organisations working to eradicate discrimination in the US, UK and India, listed below for reference:

Global

International Dalit Solidarity Network

India

Velivada: a media platform for stories about Dalits/Bahujans

Dalit Queer Project on Instagram

Ambedkarite Students Association at TISS on Facebook

National Confederation of Dalit and Adivasi Organisations

National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights

Safai Karmachari Andolan, the movement against manual scavenging

Khabar Lahariya, which I personally subscribe to, a platform for rural journalism with stories told by women from Dalit, tribal, Muslim and backward castes. You can subscribe here.

US (taken from this Google Doc)

UK

A list of Black racial justice organisations (public Google Doc)

Practical ways to support Black Lives Matter from the UK (public Google doc)

Kwanda, which I support financially, ‘a modern collection pot for black communities’.

—

Thank you to Siddharth Sreenivas for sharing the organisations working on the issue of caste discrimination in India, Ragini Menon for conversations and her thoughts, and the amazing people compiling resources for everyone to learn from and support.